It’s been two weeks since Jim Groom and I ran with the second episode of Utopian Tendencies on ds106radio, and on Friday we ran with the third episode (there’ll be a post on this soon). I’m behind on writing up the episodes but it’s shaping into a series, although we’re still finding our rhythm. So far I’ve been picking out texts and topics, sending these over to Jim and we chat about them live – you can find the recording of the second episode above.

For this episode I sent a link to the Wikipedia article on Sir Thomas More‘s book ‘Utopia’ (1516) from which the term originates, and Ingrid Burrington‘s essay ‘Effortless Slippage’ (2018).

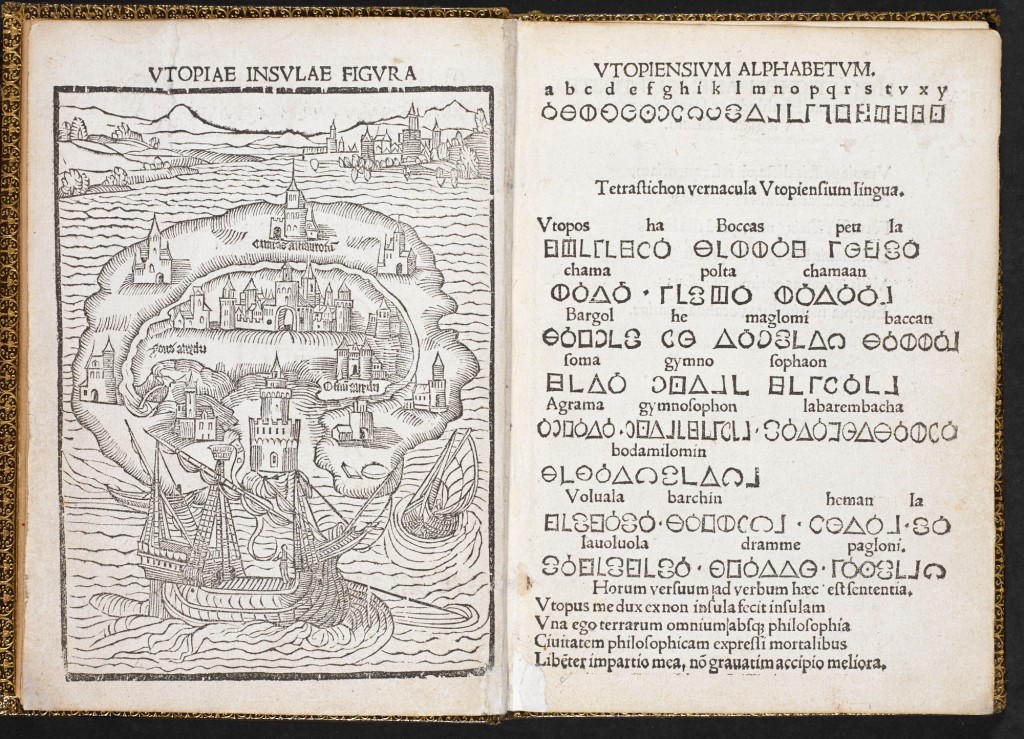

More’s fictional island of Utopia (literally meaning ‘nowhere-place’) is located in the New World off the coast of Brazil. This terra nullius setting is used to imagine how a state could be designed to best meet the needs of its people, while satirising and critiquing contemporary events in England related to enclosure of land, private property and capital punishment. I came to know of Utopia through references in documentaries and at some point read its Wikipedia article – I have not read it. But it turns out Jim studied an extract of Utopia as part of his undergrad so he was able to give more direct context of what the text is like, and contextualise it in relation to other literary and political works.

I remember enjoying finding out that “utopia” originally meant “nowhere-place” rather than its current usage as a perfect society. I mention somewhere in this or the previous episode that I find hope in art, dystopian fiction, and texts like those discussed as they expose the way things are so that they can be made sense of. A nowhere-place rather than a strict evangelical manifesto for a well designed society feels like a much more useful place to unpack how the world is and strategise how to make it better. Utopia was written at a point in European history where political science centred on how best to perform an advisory role to heads of state. More breaks from this to imagine a nation-state without need for lawyers and philosophers due to the citizenry having time for and access to education, and living under law which is easy to understand and practice by all. The island of Utopia is presented as a hopeful idea but ultimately as a society that cannot come into existence. More explores the relationship between philosophers and contemporary politics, and the duty to work within real situations and flawed systems to make them better rather than hoping to begin a world anew.

The essay ‘Effortless Slippage’ presents a history of how the internet has been visually mapped/represented and how this virtual space has come to slip into how we imagine and organise our physical world. It relates to some of the things we referenced in the first episode on: planetary scale, the promise of Web 2.0, the material impact of technology, and means of imagining new alternatives and their resulting aesthetic.

We briefly discussed in the first episode the potential edtech folks saw in Web 2.0 – Jim described initial hopes for not relying on the infrastructure of the institution and the potential of building a new aesthetic via a participatory web. And then how the work of those such as Audrey Watters and Chris Gilliard began to shine a light on our emerging digital dystopia in relation to data privacy and inequitable tech. I suppose I’m tempted by what More’s Utopia for the internet would be in our current moment – eventhough a perfect society for the internet is a “nowhere-place”, what would we imagine?

Jim picked out this ‘Effortless Slippage’ paragraph on media literacy and platform disinformation bubbles:

The tendency of users to remain in filter bubbles and propagation of myopic communities via platforms and recommendation engines has been well-documented, as has the tendency of these narrow environments to enable mass harassment, misinformation, and propaganda campaigns. In response, companies offer resources on media literacy and piecemeal hiring of content moderators or fact-checkers. But placing the onus on individuals to season their news feeds with opposing viewpoints (rather than, say, designing a platform optimised for bringing multiple viewpoints to users) or assuming the issue is the ability to critically discern sources (rather than recognising that many users are entirely media-literate but happen to hold racist or fascist beliefs) suggests platforms consider power something that the invisible hand of the market has clumsily pushed them into against their will, and not something abused in the absence of a meaningful praxis. Furthermore, it assumes that greater legibility of a user and their nuanced perspectives is a desirable outcome. Users have agency to reshape the territory of their digital bubble, but they remain mapped subjects.

I really enjoy Burrington’s expression of the complexity and multilayered ongoings of users both being trapped and nudged into particular behaviours by platforms, but also challenging the assumption that media literacy alone would prevent users from sharing in misinformation and harassment online. Those who advocate for improved media literacy do so with the want to prevent the spread of misinformation online, but would this actually meet the ends that they wish for? Social media platforms don’t care what content is shared by users, only that users continue to generate content and view the content of others’ so that they continue to view ads and generate nuanced data profiles for brokerage (“mapped subjects”). Would everyone being media literate in this environment meet the anti-racist, anti-fascist ends we are looking for? How can we challenge the existing operating model of these large platforms or provide alternate spaces? How can we support people to develop understanding of philosophical and political ideas and how they would like the world to work on their own terms? – instead of parroting propaganda they see online.

On the topic of being trapped in mapped bubbles, Jim quoted Friedrich Engels‘s description of Manchester in ‘The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844’. He then related this description to how social media platforms operate by banding subsections of society into bubbles in virtual space, and how one strata of this virtual society may not come into contact with another. Jim also linked in the work of Marxist Geographers such as David Harvey and Neil Smith, particularly on how gentrification operates and Smith’s idea of the Revanchist City. We played with the idea that 1840’s Manchester parallels 2020’s Facebook, and how enclosure operates within this new platform extra-nation-state. I mention the 1819 Peterloo Massacre in Manchester as a historical moment which spurred people to fight for male suffrage in the context of widespread poverty and disenfranchisement – and suggest that if Facebook now parallels Manchester c.1844 we need a similar moment where those that are disenfranchised fight for a voice or access to organise their own social space.

Burrington warns of defaulting to nation-state governing models and difficulties with notions of citizenship, but also warns of the “privileged prepper” who “can build her own infrastructural enclave” whilst leaving others behind. She ends ‘Effortless Slippage’ with this:

Rather than merely finding pockets of freedom in the networked SEZ archipelago, it is high time to go on the offensive—not only constructing alternative infrastructure, but mapping, sabotaging, and expropriating theirs.

In conversation we don’t come up with a utopian vision for the future of the internet – but I’m left thinking how do we work within flawed systems to lift others out of these mapped bubbles and expropriate existing infrastructures?